Once upon a time ten years, I arrived in New York city for the first time. The taxi left me and my suitcase in the middle of a chaotic midtown street. I knew barely any English and felt completely lost and unsettled. Since then I have worked my way to a state of an almost complete, not always desirable, familiarity. Prior to my arrival in Prague, my first time in Europe in a country whose language I didn´t understand, I was expecting to be again confronted with destabilizing effect. I loved Prague and even more Plasy, the small town and the people with whom I lived for a couple of weeks. It reminds me of Anchieta, the town where I lived when I was little. But I was expecting to be estranged by the new experience; in fact, I longed for it. I was not in search of postcard of the past, which incidentally I found in a local souvenir shop. It was also not the fact I encountered a place full of signs of an intense western presence that kept me from estranging the country.

I believe that, at least part of the reason for it, was the fact my position has shifted. Between my move from Brazil to the United States and my visit to Plasy from New York, a change occurred that shifted my role from that of a tourist, even if operating from the position of an artists. The question then became, how could this artist-tourist, conscious of the superficiality of his insights on the history and conditions of newly encountered site, develop a work whose pronouncements could escape such pre-determined condition? One of the possible answers, and the one I chose, was to operate a kind of displaced specificity. I worked specifically with the subject of project I have developer as a result of my involvement with the City of New York, where I currently live.

The first of these project focuses on the articulation of existent negative spaces in outdoor urban spaces. The second regards pre-existent flows through boundaries that define and regulate public areas. The displacement, aside from the differences between the cultural and historical geographies of New York and Plasy, has to do with the reconsideration of matters observed in outdoor areas they may occur in their intersection with institutional spaces.

Another tool I carried with me was the memory of an event that happened in New York not too long before my trip to the Czech Republic last September. An entire building situated on 42nd Street was dislocated a few hundred feet to its to accommodate a new commercial complex. The media focused on the technology that permitted the transporting to be realized. In my mind, the relation between this building and its history, as it developer in its original site, underwent a kind of diffraction. Had the building been moved to a completely different part of the city, this severing of the building from its foundation would immediately reveal its commodification.

The short distance of the dislocation made the reading of this objectifying operation considerably more opaque. Upon my arrival in Prague, I took my camera out and set out in my mission to capture the city in snapshots. Looking, perhaps too literally, for an entry point. I photographed many doors. More than the doors, I was interested in the numbering system of the buildings.

After a few failed attempts at asking people in the street about the double system. I finally got an answer that placated my curiosity. I was told that the blue plaque notes the number of the building in the street, while the red locates the building in a specific area of the city. I did not research the history of the implementation of this system; in my quick evaluation it seemed to combine both a relative and an absolute way of administering space.

This is a level of precision I had not seen in either Brazil or in the U.S. In Plzen, a city between Prague and my final destination, I saw speakers directly attached to the facade of buildings. Most of them, I found in a street named America: perhaps it was not an ironic coincidence that in the same street I also found McDonalds’s and other staples of international franchises. This time I didn´t ask anybody why there were speakers placed outside on the streets.

My initial thought was that they were a means for business to advertise their goods. But not every facade was of an establishment. And why would they be linked to wires that seemed to connect them together to possibly central system? Unless the speakers are there to facilitate direct communication with passers-by. My mind immediately wondered in a fictional dialogue that I began to have with a city administrator who already knew my name.

I became a paranoid tourist and decided to escape the grid in which the speakers were deployed. And I got lost. I have to say I take a special pleasure at walking without direction in a place I absolutely don´t know. I feel more connected when I am lost, less topical, more integrated to the place, even if by means of misunderstanding it completely. Then I saw the train station. I tis hard to talk about this moment without fetishizing it. I was absolutely fascinated with this building, beginning with its facade that seemed to be part of a past that was not interrupted by the present. It still sounds a bit magical. I will try to be more objective.

Perhaps it was a combination of its old colours that didn´t seem to be even a bit faded with its well cared while not polished state that made it seem antique and actual at the same time. In that building, in another day I had my definitive experience of estrangement. I had just missed the train and went to the person behind the counter to ask her when and if there was another train that same night. We could not communicate and she pointed to a place behind and above my head. In that direction I could only see the board with the train schedule, but Plasy was not listed.

I kept going back to her and she kept pointing in the same direction. I looked around in vain for other people, whom I could ask the question. I felt alienated, alone, surrounded by signs I couldn´t read and people I couldn´t talk to. Just a few days before, a worker from the train station told me that photographs were not allowed, I was trying to take a snapshot of an interesting vertical rolling panel, the same one I now found so strange. The feeling lasted for almost an hour, while I also tried to use the phone without success. Then I walked up the stairs to the second floor of the station. And I saw the sign for the international information booth. That´s what she was pointing toward.

Everything found its place again. I never went back to photograph the train station; there was nothing on the surface of an image that could registered the experience I had there. The tourist in me died there, at the moment when the same exact space went from appearing to be absolutely strange to feeling completely familiar. The same process I lived over the course of my ten years, I experienced in a very compressed way over the course of an hour. Not the space, but my relationship to it was altered by means of a renewed understanding of it. Language was the mediating pivot of that experience. Next and final stop: Plasy. The place I stayed is an old monastery that, I am told, was a tone point occupied by the Nazis. I tis now partially used by an artist´s residency program, the Center for Metamedia. Part of the complex, once also used by the Center, is now undergoing renovation under auspices of the Czech ministry of culture.

During my stay at the Center for a symposium on the contemporary conditions of narrative, I witnessed a moment of tension between the two groups. Unfortunately, the situation was triggered by the artists´ use of the space; more precisely, by a usage of the space not in conformity with the prescribed set of rules. One rule in particular was not followed in its full extension: the rule that said that the spaces should be locked at all times.

One evening, the door of one of the spaces was left unlocked and unattended for short period of time, a fact that was spotted by the gatekeeper. The next day, a couple of keepers came to the Center and formalized the removal of the key of the particular space from the hands of the people who run the program. It was a very sad moment, I remembered the mixed feelings of us all. First, of sorry for causing such problem to our wonderful host, people who had received us with great generosity and hospitality.

But also a feeling of being disproportionately punished without any resort to communication. In face of certain absurdity in this use of power I wondered why didn´t they take over the whole building, what just one door out of many in the very same building? Why would they be so specific in their determination? It seemed to me that the people at the center were being inched out, subject to a type of pressure that will eventually become intolerable. At such point they might as well leave the place on their own will, unable to function under a very arbitrary code of security. And that would be accomplished somewhat by a process of „natural selection.“

This event, that illustrates what I have interpreted as a gradual pressure to promote displacement, has informed my intervention on the site. The other significant case is the one that I mentioned before, of building moved by a few hundred feet on the same street in New York. Both involve precise and relatively limited operations. I began to think of a way of re-articulating this notion of a subtle displacement. I choose to work on the facade of a building that is part of a group of four and is located at the intersection between the ones being renovated and the where the artists and volunteers for the program reside. The facade itself had the opening in its doors and window sealed off with cement, stripping it of its functionality by returning it to the simpler form f a wall. Oddly, the transformation was not complete, the outlines of the window and the whole portal and steps of the door were not removed; what was left was neither a wall nor a facade.

The same was the case with the white paint used as a wash over the whole surface. It was enough to set the area apart from the old-yellow coloured walls and facades of all the other buildings. But not sufficiently opaque to obliterate the still very pronounced outlines. The unfinished way in which both cement and paint were applied suggests a deliberately failed attempt to erase the face of the building. Another particularity is that the building can only be accessed through its side door, unless one breaks into the space through the window. Each artist was assigned a key for the space of their choosing with the condition that the key would be returned to the office when the artist was not using the space. With almost thirty people living and working together in a very large space, the keas were, more often than not, in transit.

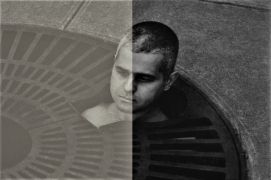

Initially, the decision of breaking into the space was a matter of necessity; I needed to go inside and didn´t have the keys for the door. Going through the window seemed liked the next logical step. Soon, I realized the significance of this activity in the specific context I just described. The window has a double set of panes, one opening to the outside, the other to the inside. In the middle there are crossed iron bars with a relatively small cut out opening near the base of the window. I planned on passing my body through that opening without being sure of the feasibility of that action. What follows in the uncut video I made of this experience focuses primarily in the tension between my body and the detergent bars in the window. I projected this video in actual size back onto the building. But displaced its original location by a few hundred inches and located it exactly over the outline of the once existing window on the „blank“ fasade.

Alex Villar, 1999, Plasy

Alex Villar was born in Brazil 1962, resides in New York. Working between performance, video, and photography, Villar poetically and humorously explores the hidden sites of power and spaces of survival in contemporary life. He has been featured in exhibitions in the New Museum, Mass MoCA, Drawing Center, The Menil Collection, Exit Art, Art in General, Apexart, Dorsky Gallery, Museu de Arte Moderna, Paço Imperial, Funarte, the Institute of International Visual Arts, Whitworth Art Gallery, Hansberg/Woolf Gallery, the Göteborg Konstmuseum, Signal, Mediations Biennale, Galeria Arsenal, Marco Museum, Halle fur Kunst, Beirut Art Center, and Zendai Moma. Villar studied at Hunter College, the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program, Hélio Alonso College, and Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage, and he has received grants from The Edward and Sally Van Lier Fund of the New York Community Trust, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Office for Contemporary Art Norway, Danish Arts Council, and the New York Foundation for the Arts.

Drawing from interdisciplinary theoretical sources and employing video-based, performative actions, installation and photography, I have developed a practice that focuses on the intersection of processes of subjectification and the actual spaces of everyday life. My interventions are done primarily in public spaces. They consist in engaging situations where the codes that regulate the daily usage of the public spaces of the city can be made explicit. The body is often made to conform to the limitations of claustrophobic spaces, therefore accentuating arbitrary boundaries and possibly subverting them. A sense of absurdity permeates the work, counterpoising irrational behavior to the instrumental logic of the city’s design.

Theoretical ideas informing my work include a number of texts on the problematic of space. Particularly relevant is the work of Michel Foucault on panopticism and heterotopic space, but also Michel de Certau's work on the rewriting of the spatial text through common usage. Aesthetic traditions foregrounding my work range from the sixties and seventies performative-based sculpture and installations by Helio Oiticica, Ligia Clark and Cildo Meirelles to the urban strategies of the Situationists and the anarchitecture of Gordon Matta-Clark. Like the in-between activities it seeks to investigate, my work lives between various fields: part nomadic architecture, part intangible sculpture and part performance without spectacle.