"The installation of Baudouin Oosterlynck for 'Hermit' in Plasy consists of pictorial documentation about his work with sound and of five transparent masks which hang from the ceiling in one space of the granary. Some of the masks have their ears open, some their mouth or eyes. Every visitor can, by putting on the mask, prove the changed conditions of our perception."

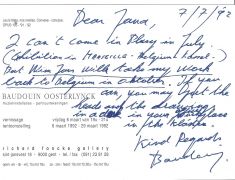

Baudouin Oosterlynck, Plasy, 1992

Baudouin Oosterlynck is a sound artist living in Belgium. He has not only composed noteworthy works (recorded on CD and long playing records, some of which are available at present from Metaphone), but he is also the editor of two important books containing statements by experimental composers in Belgium. Last but not least, he has undertaken research into the specificities of sounds related to and issuing from specific locations, both in ordinary places, in the streets and back alleys at home, and during his travels where he was listening, for instance, to the sounds of the wind brushing the earth and rocks of the Spanish highlands, and to the noises of places close to the Norwegian North Cape.

His conclusion or credo is very pertinent: “Je tiens toujours compte des particulatés acoustiques du lieu où se deroule la manifestation [sonore].” “I always pay attention to the acoustic particularities of the place where the [sound] manifestation takes place..." Where it develops…

Such attention to the particularities of place, to the intimate relationship between the material aspects of place, space and sound could not but turn ‘situationist,’ in a way. That is to say, attentive to the specificity of situations. And certainly more in the sense that Jean-Paul Sartre awarded to this word than in the slightly different sense preferred by Guy Debord.

We are situated, as human beings, but that implies that our actions, that the results of our creative production, that our discoveries of man-made as well as natural phenomena (and their interaction) are also situated. Situated in space, time, history, a particular society. An exploration into the realm of located sound(s), of sound(s) traversing not abstract but concrete space, architectural space, street space, space in nature today, is an activity that is always situated. And, in the case of Baudouin Oosterlynck, it has unearthed in him, as a progressive artist, a desire from which has sprung a goal, a task, a project: “faire entendre ces situations d’ecoute...” To let others “understand these situations of listening.”

Not surprisingly, it also enticed him to developing specific ‘hearing aids’ or ‘instruments of listening’ (‘instruments d’écoute’).

They range from the stethoscope to curious objects, attached to the ear (or ears): ‘instruments’ that open up to the sounds like large funnels, like horns that are similar, in a way, to the horn of old gramophones.

Sooner or later it was inevitable for him that such instruments evolved into a large array of even more varied ‘objects’: Objects that are instruments of listening and instruments of playing at the same time. Things that are producing as yet undiscovered, new, otherwise unknown sounds.

Facing such objects we often discover that, due to the attached stethoscopes, it is always the player who is the only possible audience. And thus, listening, actively receiving, becoming aware of sounds, becomes as important as playing, if not more important. To quote the artist and experimenting inventor of these instruments once more: “La façon dont les gens reçoivent la musique est plus importante que la musique. Je crois que c’est l’essentiel” (“The way in which people receive the music is more important than the music. I believe that this is exactly that which is essential”).

This is a political and philosophical position seldom shared today by artists and other people in the ‘milieu’ of culture where the contemporary Capitalist ‘culture industry’ – Kulturindustrie, as Adorno called it – attempts, by all means, to fortify the separation between the roles of ‘producer’ and ‘consumer,’ between the supposedly exclusively active artist, musician, inventor etc., and the supposedly passive, ‘consuming,’ ‘entertained’ recipient.

In contrast to the still dominating tendencies of a mediocre and stultifying Capitalist ‘culture industry’ brandishing more than ever a silly mock-diversity (of fashions and marketable trends) that can justly be said to camouflage the on-going homogenization inscribed into a globalized mode of consumerist ‘introduction to art’ and entertainment in the arts (reaching from MTV to MOMA, from ARTE [the TV station] and the CENTRE POMPIDOU to art fairs across the world – Shanghai certainly being included), subversive artists have chosen very clearly to practice art as a means of activation of the public and of inclusion. Already before the Second World War, the left-wing playright Bertolt Brecht was bent on breaking down the barrier that separates the performing actor from the public. With respect to his dialectic plays that posed questions in order to stimulate the quest to think and to discover in the audience, Brecht even hoped that the actors would at the same time be the discovering audience. There was perhaps no need for an audience beyond this, but a need for everyone in society to become actor and audience at the same time.

With regard to sculptures in the public sphere, Jochen Gerz has lately affirmed the same position. And I think that Baudouin Oosterlynck, in the course of his creative evolution and experimentation, has come to embrace this position, as well.

By inducing people, ordinary folk outside the musical professions, to produce and discover sounds never heard by them before, Oosterlynck is practicing an approach as a sound artist that is both radically democratic and fundamentally anarchist. At the same time, he steps out of the limelight as experimenting artist, as inventor in the field of “sound art” because (as John Cage would have said too), the individual sound artist or composer is not that important, at all. What matters is the discovery of sounds. Of music, that is. And the liberation of the listeners, the people, who discover their potential as creators, by becoming creative listeners, actice receivers and searching creators at the same time.

Just as liberated theater that was tearing down the distinction between ‘actors’ and ‘the public,’ such liberated sound art becomes a socioculturally significant field of experimentation and a model for a liberated society in which the hierarchy between rulers and ruled, classe politique and voters, experts and laymen, bosses or managers and workers is no longer taken for granted. Where, in other words, such hierarchies no longer apply but are thrown on the scrapyard of history where they finally, after all, deserve to wither away for good.

Taken from Andreas Weiland, "Baudouin Oosterlynck: A Sound Artist Who is Setting People Free to Discover the World’s Sounds"