A fragment of an interview with Miloš Vojtěchovský conducted by Lenka Dolanová in 2011 for the anthology of texts Ostrovy odporu, 2012, National Gallery in Prague

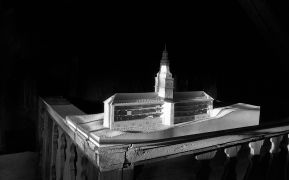

For a total of eight years from 1992 to 1999, the monastery in Plasy was one of the first places in the former Czechoslovakia to hold artist residencies. The project gradually developed into regular, sometimes theme-based meeting sessions for international groups of artists, theoreticians and curators, and became part of various interdisciplinary symposia and exhibitions. How did this concept come about and why, of all places, choose the monastery in Plasy?

It came about in the right way — by chance. The painter Jiří Kornatovský, who comes from Plasy, had an exhibition at the OKO Gallery, which I had attempted to run from 1989-1991 in Amsterdam where I lived since the 1980s. He mentioned that there was a chance to put on an exhibition in the monastery there. I had been at the legendary exhibition 9x9 in Plasy organized in 1981 by Anna Fárová, and had vivid memories of that place, even though I knew everything would be probably different by the 1990s.

In the winter of 1991 I made a trip there to take a look. With the help of Jana Šikýřová, the monastery’s caretaker at that time, Kornatovský intended to hang some pictures in the room next to the Saint Benedict Chapel, which at the time served as a provisional exhibition space. I suggested changing the concept: it seemed a shame to me to just bring and exhibit pictures or sculptures there. I borrowed a video camera from my friend Tjebbe van Tijen, travelled to Plasy in winter, recorded what the spaces looked like and then showed the video in Amsterdam to some friends who were squatters and people from art communities, rather than to people from the “high art” circles.

My hazy idea was that we must do “something” in the monastery — maybe an installation or a concert. I didn’t have any money for this, but at that time the bus trip from Amsterdam to Prague wasn’t that expensive. As I was recording with the video camera, I noticed again the space’s excellent acoustics. It seemed to me that it would also be good to consider starting to work there with sound. I recalled that in 1981 accordionist Jim Čert-Horáček and Jiří Stivín had played at the St. Benedict Chapel, and I had been amazed how Jan Blažej Santini had designed the convent’s acoustics so brilliantly. The caretaker Jana Šikýřová, Jiří Kornatovský and I agreed in the end that some guests could come starting in the spring and that in June we would organize something like a jamboree, or a symposium. The first year’s symposium proliferated through a chain reaction and there were some fifty or sixty people participating. I managed to get Jiří Zemánek involved as well, and he spread the word to people he knew.

The idea for a “residency” was influenced by the fact that one of the proposed participants, the sound artist Bram Cox, was blind and arrived with her husband Mathias Klijn, who was visual artist, disabled and in a wheelchair. They agreed with the filmmaker Joost Verhey who was shooting a documentary about them that they would drive to Plasy and shoot the film there as well. The caretaker kindly arranged provisional accommodations for them in the prelature building which had just been abandoned by the Civil Defence division of the Ministry of Defence, and which offered several large empty, shabby rooms. So, suddenly there was the possibility of accommodation; others moved in and some guests even camped out inside the convent itself in the first year. The degree of freedom, or lack of control was unbelievable; this very much surprised me even though Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s was a country of “unlimited possibilities.”

The concept was created and developed quite spontaneously. Eventually larger groups of artists from all over the world would make their way each year to Plasy for several weeks or months.

It was mainly during the first two years that it happened spontaneously. It ended up that, for instance, one of the attendees from Amsterdam remained in Plasy until the beginning of winter. Most of the guests were enchanted by the place, by the desolate beauty of the abandoned large monastery. This motivated me to begin preparing for next year. I managed to receive a grant of 2,000 guldens (about CZK 40,000 at the time) from the Mondrian Stichting, the Dutch cultural foundation, which we used for a catalogue that Joska Skalník did the typographic work for. Thanks to the catalogue and word-of-mouth, the legend of Hermit and Plasy spread and more people expressed their interest in coming. It was a time of euphoria that stemmed from the reconnection to Europe and a desire to take a look at what it looked like behind the Iron Curtain.

Were you inspired by any similar activities that you had attended before?

I had never had a similar experience and had never been to any residency, but I would often visit events related to residences or unofficial activities organized by the art community in the Netherlands. Probably the greatest inspiration for me was the experience from the Het Apollohuis space run by Paul and Heléne Panhuysen in Eindhoven. Various art communities in squats in Amsterdam, such as Aorta or Silo, which disappeared long ago, or Melkfabriek in Den Bosch and De Fabriek in Eindhoven, or my short visit and stay in the Christiania community in Copenhagen, or the Polish Construction in Process network were also inspirational. People from similar communities began to come to Plasy.

I remember that Woody Vasulka, whom I had met about two years before in Amsterdam, declared that refuges for artists have to be maintained all over the world; a place to come and work; a place that is operated in a kind of non-monetary, post-capitalist parallel economic system based on donations, sharing and friendship. I was quite taken by this idea at the time. It seemed like a great idea to actively take part in something similar in “Czekhistan.” I also felt that the right time had come to try connecting and gauging experiences and ways of thinking and doing between Western and Eastern Europe. I still felt a certain resentment about this. Plasy was about a hundred kilometers from the western border, which seemed to me geographically appropriate as well. Recollections of some local, unofficial events also understandably played a role — such as the aforementioned 9x9 photography exhibition in Plasy, or the Čestmír Suška’s and Luboš Fidler´s symposia on a farm in Malechov near Klatovy.

Later, the Hermit Foundation was founded as a kind of institutional anchoring of the entire project.

We founded the Hermit Foundation for prosaic reasons in order to be able to apply for grants and so that we could have some kind of sponsorship when negotiating with the State Heritage Institute, the keeper of the building at that time. I established the foundation with Jiří Kornatovský, and later with his brother Ivo and with Jana Šikýřová.

The Hermit’s activities in Plasy are often presented by thematic circles and inspirations that refer to the foundation’s title, i.e. to the hermitage and the tradition of hermeticism. The idea of a certain exclusive, relatively closed community existing in a somewhat separate space, adrift from the rest of the world, comes up repeatedly in connection with Hermit. And it’s still written and spoken of in this way today. In what sense did these traditions actually form the Hermit project and the activities in Plasy?

This is a myth about Hermit that was created by others. I presume that I myself didn’t sustain it, although it is true that I was playing with themes of hermeticism and alchemy at that time. And the venue was indeed a former monastery, though it had been long — roughly 200 years ago — been shut down, abolished by Josef II. At the time, the term “hermit” seemed to me to be the most appropriate framework. I also played with the idea of hermeticism, since the Baroque spirit of the architecture is still stronger there than the Metternich influence from the 19th century (Klemens von Metternich obtained Plasy in 1826) and was in my view a determining factor for the entire framework of the programme. But the reputation of a closed community is an unfounded notion. Maybe it came from the fact that Plasy was then a practically unknown place and few knew where it actually was. But I welcomed being able to do something outside of Prague, outside the tourist hustle and bustle that prevails there. It occurred to me that changes are slower in the countryside, a hundred kilometres outside of Prague.

In terms of what the event would consist of, I considered it an open framework from the start. Someone came to visit unannounced and stayed a month. Plasy was not directly linked to any established cultural activities in Prague or in Plzeň; it was therefore beyond the horizon of the general art society’s interest and habits. It was far away and most distinguished curators didn’t travel there. Actually, hermeticism and “closedness” do not mean the same thing — and the hermitage tradition is something else altogether.

I was reading at that time an essay by Peter Lamborn Wilson , a.k.a. Hakim Bey, on pirates and temporary autonomous zones, and I liked how he poetically and amusingly links the context of the hermetic sciences and religious Medieval heretics to today’s radical culture of protest. In studying the books of Johan Amos Comenius, about whom, in 1991, I started to prepare the exhibition project Orbis Pictus Revised commissioned for the ZKM Centre in Karlsruhe, I came across the fascinating figure of the Jesuit priest Athanasius Kircher and was captivated by the illustrations from his books. I also read a book about the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, founded by David Hildebrand Wilson. I maintained a friendship with Vladislav Zadrobílek, who founded the Trigon publishing house which was geared towards, among other things, the publishing of books about hermeticism and occultism.

But soon we had to close down the Hermit Foundation anyway, since the state passed a law which stated that a foundation must have assets of at least a million crowns to be considered a foundation. We therefore founded the civic association The Society of Friends of Art in Plasy. Around 1995 I also began to introduce the name The Centre for Metamedia; I am aware this was a somewhat enigmatic and pretentious term but, for poetic and strategic reasons, something which sounded exotic was useful. I thought up the term and felt that it nicely captured the hybrid situation that, more or less, is not based on objects, instruments or disciplines, but on hybridity, access, content and openness. Something like the antithesis of the entrenched professional art symposia where sculptors sculpt and drink together in quarries, ceramists bake clay together in kilns or landscape artists paint landscapes together.

So the idea of a kind of closed society was created only retrospectively? Let me quote from something you wrote: “This initiative was an attempt to see how a community works within a secluded, closed system; a unit that was autonomous. What it was like before and what it could be like. The community is simply religious or artistic, but it’s still a community.” Perhaps that idea comes from the fact that the Plasy project lacked a more extensive reflection from the Czech environment at that time; in 2007 Radoslava Schmelzová wrote her thesis on it for the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, but otherwise not much has been written about it. And since there isn’t much material, what has been written and said has been taken far too literally. Consequently, Plasy is slightly made up of myths and exists more or less only in the memories of the people who attended it. Those people often speak of it as if what took place there is, to a large degree, incommunicable.

That’s true, but your quote reflects more the concept that I started from. At any rate, the people attending the symposiums were for a certain time outside the centre, in an unknown terrain. The bus trip to Plzeň was nearly an hour, and it took two and a half hours to get to Prague. Most people around there spoke only Czech, so the place really did have a remote feel to it. A kind of community consciousness and even friendship must have gradually developed there. On the other hand, many people were visiting; in the early 1990s there weren’t many of these types of events taking place.

Visitors came from Prague, but also from many places in western Bohemia, from Moravia and abroad. Sometimes two to three hundred people attended the concerts, symposia and weekend activities. But this was beyond the capacity: when so many people started coming and attending it became a little unsettling. A different feeling of community started to develop in which people were approaching it as a party.

Which of the themes of the symposia do you consider to be most important from today’s perspective? Their titles were: Letokruhy (Tree Rings, 1993), Průsvitný posel (Transparent Messenger, 1994), Fungus: průzkum místa (1145-1995) (Fungus: Exploring a Place (1145 — 1995) 1994), Hermit V: Křížení poledníků (Hermit V: Meridian Crossings, 1995), Subrosa (1996), O počátku (About the Beginning, 1997), Limbo 1 (1998) and Pohádky (Fairytales, 1999). They focused on, among other things, the Baroque heritage, on figures that had lived in Plasy and, perhaps even in a certain ecological sense, how they had interpreted their given environment. Could you expand on some of these themes and, above all, on how the artists and other participants approached them?

Each year it was a little different and depended on various circumstances. I think that both subjectively and objectively, the most interesting and the most successful was Meridian Crossings in 1995. This one actually didn’t have any theme, only a kind of vague cosmological metaphor on the antithesis of elements in terms of the north and south, of heat and cold. Though we didn’t have much money for the symposium, the synergy of the diverse community that came together there was incredibly harmonious. At that time we were still able to work in all the spaces of the monastery complex, which seemed to be instilled and animated with new life. We were able, intuitively, to set up a situation in which those who came there — from sculptors to musicians — did not remain stuck in stereotypes, but complemented one another as well as the whole environment. In the evenings a visitor could wander in the ambits of the convent, sometimes disappearing into hidden rooms, listening to the eerie underground sounds, or sit in the Elysian courtyard, watch the inflatable white swans in the cellars under the granary, or climb up the bell tower and look out over the countryside. The autumn symposium Fungus was so magical because barely anyone came to the opening of the exhibition and conference. The ecological idea of that symposium was not my idea, but arose from a discussion with co-curators from Belgium, Holland and Germany.

Looking back now, how do you perceive your role in Plasy as a main organizer of sorts who, in a way, directed the whole event? The chances are that not everyone who wanted to come was allowed to come — wasn’t there some kind of selection process?

In the beginning, especially the first two years, I or the others did invite people while others signed up. In time, I looked for an assistant to help with the preparations. Since nobody similar was available actually in Plasy, I approached Jiří Zemánek, who worked as a curator in the National Gallery and who was quite active at that time. He helped me to find other people whom I didn’t personally know. Eventually, a selection had to be made since the amount of work and responsibilities began to be unmanageable.

At the beginning of 1995, after the first three years of the event, we sent out a call for projects to be submitted for the next year. We rejected a few local projects on the grounds of being unrealistic or too feeble. Perhaps that rejection caused rather unfriendly reactions. I knew that there were whispers that we were putting on the event “just for ourselves.” But I don’t think that was true. I wasn’t there as a curator with a vision, dictating who and what would be there and who wouldn’t, but more as a mediator and catalyser trying to arrange with the caretaker and heritage staff what was possible and feasible. If people had been just a little flexible and accommodating, then they could have taken part in exhibitions.

The diversity of music genres was also broad: from Slovak folklore to Baroque music and contemporary electro-acoustic styles. Quickly, I began to realize that personal taste is limiting — at least here where something more than purely an art project was taking place. We had to consider the local people as well — that we could not frighten them off with “avant-garde” art, which was obviously frequently there, and sometimes quite harsh and radical. The space at that time was still very dilapidated, quite different from the Plasy monastery site today. Actually, it was a bit more apocalyptic at the time; especially combined with the regular pop-rock concerts that were held in the fields and where several thousands of fans of the local group Brutus gathered and occupied the little town.

Is it possible to explain how the selection of artists was profiled? From the catalogues it is apparent that you focused on site-specific projects situated directly in the monastery’s space, as well as on the aforementioned acoustic art. Was there a clearer conception behind it? In what way did it succeed or fail in being carried out?

The “production” was done without a plan and more through natural selection. Sometimes I liked it when a particular person came, even if in the end I wasn’t convinced that what he had done had completely worked out. My task was to provide assistance for this work. We tried to convince everyone who came there not to just launch into their work and not to simply realize an idea and project that they’d originally come to Hermit with. That was against most laws of professionalism as cultivated at the academies. But most of them turned out poorly when the guest just started working on his/her piece without first taking a look around. On the other hand, the “interventions” of those who were willing to wait a few days were more sensitive and successful. In retrospect, I see that the project’s greatest asset was the fostering of improvisation. Well-established artists took part which, in such an environment, was of ephemeral value, but also beginners, students and amateurs contributed. Nevertheless, it usually all worked out together, and if you had the sentiment and ability to seek content instead of well-known names, it was an interesting experience. The concept consisted mainly of the art of suppressing one’s own ego and, even if it sounds awkward today, “establishing a dialogue” with the whole environment, including the architecture, landscape, social context, other people.

The artists usually stayed there for a longer time —

Whoever could, did, but from the start the accommodations were quite basic — there was no shower, we didn’t have beds, no facilities such as a kitchen. Guests stayed in nearby tourist cottages or at a scout camp. Everything gradually developed as long as we had funding for it. But we didn’t receive such money until 1996 when the Pro Helvetia foundation provided a three-year grant thanks to the kind help of the local director Iren Stehli. When someone who required higher standards came, they were able to stay at the school, which was empty during the summer. Some stayed three months, some a week. From the biggest names, I think Roman Signer stayed for only four days, Jimmie Durham ten days, Fred Frith four days; Ulay for two weeks, Paul Panhuysen, Paul DeMarinis, Alistair McLennan — they all stayed as long as they felt necessary. A regular residency was set for a month, over the winter up to three months. From 1996 we had a secured budget, and could even pay the staff (Ivo Kornatovský, Jo Williams, SIďa Sidorjak, Martina Tomášková) and for materials for our guests — before that, the guests paid for everything including travel expenses and food.

Only then could we officially call it an artist residency; we were paying for accommodation for the invited guests, meaning a shared bedroom, shared kitchen, two showers, darkroom and an equipped workshop. We were able to provide pocket money to some and others had to come up with their own money. Food was usually included in the overhead costs and sometimes the guests themselves took care of the rest. The residencies were officially held from 1995 to 1999. During the summer when the symposium was held, up to sixty “hermits” stayed on the premises in the new and old building of the prelature.

Was it assumed that everyone would create something that would be presentable for visitors, or did it depend wholly on the individual artists and on how they would interpret and make use of their residency?

It depended on the situation. Some people merely came to help with the organization. We offered them food and a place to sleep — there was always plenty of work to do in the monastery. Other activities that were not necessarily accessible to the public, similar to workshops, were also held. Starting in 1996, after having hosted a range of guests, I began to consider opening the programme in Plasy to other professions, to those not necessarily belonging to the artistic community. I also tried to involve social projects or to invite researchers from the natural sciences and humanities. It slowly began to work. Some came for a lecture, others stayed a week. Performers, those involved in theatre, dancers, musicians, painters, sculptors and sound artists, writers, all came. There were writers — for instance from Greece, the United States or through the Soros Foundation from Eastern Europe — who worked there on publications and often had their own means of support from other sources. For some, Plasy literally became a refuge. The artist Avdej Ter Oganian, for instance, who had just escaped trial in Russia, spent his first two months in Plasy as he had nowhere else to live.

The project came to an end mainly due to disagreements with the Plzeň Heritage Institute —

This had more complex causes and various circumstances played a role in this. Essentially, I devoted several years of full time work to Hermit. I wasn’t able to make a living or provide for my family, and I didn’t feel right about making this the main source of my livelihood. I needed to find different work elsewhere in the Czech Republic, and so I accepted the offer of a job as curator at the National Gallery in the Trade Fair Palace. I worked there for about three years, starting in 1996 or 1997.

At the same time, I was hoping to gradually involve others, mainly local people, in Hermit; people who would take up the initiative and part of the responsibility. But I wasn’t able to do this. Paradoxically, a more stifling atmosphere set in starting in 1996 when we received money from Pro Helvetia. Considering local conditions, it was a decent budget. The former director of the Heritage Institute was negative from the beginning. Since we also had some support from the Ministry of Culture where Věra Jirousová supported Hermit, I guess he was worried that if he threw us out or was too hard on us the ministry would get upset with him. He dictated the conditions as such that we paid an annual rent of CZK 250,000 to the National Heritage Institute of Western Bohemia in Plzeň, and on top of that paid for the accommodations of everyone who spent the night in the prelature. The director’s supervision of the new caretakers caused the original openness and open-mindedness of the space to disappear and a kind of bitterness set in. While Plasy received quite a positive response from abroad, I felt we didn’t find real support in our own country. Perhaps it was also because the political structure and personnel changed at the Ministry of Culture. We always had to provide very complicated reports on costs for the grant. Once, we even had to return money because someone at the Ministry of Culture didn’t like the accounting statement on costs, as it didn’t correspond to the given accounting columns. It was an unpleasant feeling since we had to pay so much to a state institution with the money designed for the project’s development, which I felt increasingly at odds with. This was money that the project development was to be financed with.

In 1999 I decided to give up and withdraw from the project. The program in Plasy had the momentum to continue on for some time. Students from the Academy of Art, Architecture and Design in Prague, from the Fine Art Academy in Prague or the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Brno University of Technology were used to going there with their teachers for workshops. On the other hand, during the last two or three years before our operation came to an end, regional artists and sculptors were cramming in there and using chainsaws and welding for two weeks and placing their dreadful iron constructions everywhere. This was done under the patronage and with the blessing of the Heritage Institute as a counter action against Hermit. When I looked around, I saw the result of the sculpting or painting symposia in which gaudy paintings were hanging in the cloisters, while we were no longer able to put up anything as it, supposedly, marred the convent, while they hammered hooks and placed scrap iron all round. I had enough.

The fact of the matter is that the space itself was getting drained of its energy and overrun with art, and so I thought it was time to back out. It was a personal failure with an enterprise that I felt bound to. I had tried to fool myself into thinking that we would build something positive, both locally and perhaps even globally. These were naive and utopian ideas.

** So you felt that the residential project in Plasy could be long-term. How do you rate the importance of Plasy now, looking back more than ten years?**

I personally believed that it was an important event. Particularly in the beginning of the 1990 s I personally found it great that people from different cultures and with different views could meet somewhere in a quiet place. I assumed that now, when the wall had finally collapsed and the divided communities were rejoined, new times would arrive with a change of spirit that would lead to a cross-empowerment of those qualities which were positive in both the East and West. I was somewhat critical of my experiences of living in the West, and I hoped that when the political borders fell, a mutual catharsis would take place. The establishing and maintaining of locations like Plasy could at least contribute to the kind of spiritual transformation that Fritjof Capra, Rupert Sheldrake or David Bohm spoke of. Ha, ha.

I didn’t see this as some kind of fishy new age futurology, but, instead, a kind of retrospection — a glimpse of the past. In a certain way I also considered Hermit as a chance for getting feedback, as a vehicle for a general revision of modernism, and an attempt to understand the monastery’s old meaning and significance for the place — the Cistercians had once built here a spiritual and economic base in the wilderness. It should be said however that from today’s perspective, this sometimes consisted of quite a forced colonisation. I thought that such a network of “enlightened” friendly places could be created, and after half a century of massive colonisation, destruction and militarism, could serve as a base of something positive — both for people and nature. What’s more, the Plasy Monastery possesses remarkable energy.

But if Hermit had not been smothered by the pressure from the Heritage Institute, do you think that it would have somehow been transformed? What did you think it would be like if it continued?

I saw two possible alternatives. One consisted in attempting to preserve the original degree of openness and spontaneity. That would require a group of people who together could develop the project’s idea and share a common vision for its direction. Or, to shift towards professionalism, to establish an institution and thus integrate the project into a kind of framework that would have to have relations to local structures, to the Plzeň Region, to West Bohemia. All this obviously would require management, diplomacy and lobbying abilities. And those are not my strongest points.

Could it be said that the community network that was created there still works in some ways today? Did other institutions take up the Plasy idea? Were any of the themes developed further?

I’m not so sure about the community. People forged friendships that often still endure. They met in an unusual situation in which they were forced to cooperate, whereas the art business demands competitiveness, self-promotion and self-centeredness. You had to speak with people, let something about yourself be known; it wasn’t the kind of communication you find at an exhibition opening where masks and social games prevail. When you live in a single building and not in a hotel, and you have to clean up and wash the dishes, or to cook for others, you’re in a slightly different situation. A community in the sense of a kind of ideologically kindred commune or organized network was certainly not cultivated there — it was rather a kind of network of friendships and long-term collaboration which stabilized over those few years. A few kindred events and projects took up, adapted and implemented our system of organization elsewhere — in other countries and situations.

From today’s perspective, what is Plasy’s legacy? Which of the themes developed there has proved to be important, essential, or inspiring for further development and for your own work?

One thing that was created at about the time, and I feel was perhaps influenced by the Plasy spirit, was Cesta, the cultural centre in Tábor. One of the centre’s founders, the American Chris Rankin, came to Plasy — I think it was in 1993 or 1994. At that time he and Hillary Binder founded their own art project in an old mill. In Plasy we also organized a workshop on autonomous cultural projects initiated by artists. A number of people from all over the Czech Republic — Kadaň, Brno, Ostrava — came there at that time (1995 or 1996) and tried to establish something similar. Later, an art centre in Broumov was established by Petr Bergman, but after a few years that also fell apart; just like the annual summer symposia in the monastery in Bechyně, or Mecca - the Central European Art Colony in Terezín.

The Klatovy/Klenová Gallery project was also, I believe, influenced by Hermit. Helena Hrdličková, who was a curator there in the 1990s, regularly attended the symposia and festivals at Plasy. Klenová is a model case in which they were able to infuse a state institution with a similar atmosphere while preserving the feeling of a free space. They also started to organize student residencies, concerts, and opened the granary as an exhibition space. That’s a good example of how something was at least temporarily carried out successfully. Something like that still exists during the summer in Mnichovo Hradiště and certainly elsewhere. Perhaps the greatest benefit for me was encountering the sovereign architecture of Santini’s monastery and meeting with many rare and interesting people who had the chance to attend.

Was the different approach by people from abroad (initially mainly from the Netherlands) noticeable, and did people from Czechoslovakia perceive and approach the space and communication in a completely different way?

This was undoubtedly the case in the beginning. Yet it wasn’t by any means just the Dutch who attended; people from all over the world came. I tried to get guests and artists from exotic, far-away countries such as Japan, India, from Australia, Latin America, and even an African came, which at the time created quite a stir at Plasy. In the early 1990s, many Czechs lacked confidence to a certain degree; they often didn’t speak English, but at the same time wanted to meet foreigners. Until 1989 the opportunity in our country to make international contacts was more of a rare privilege — otherwise a mono-culture prevailed here. In the beginning, the people of Plasy were curious since foreigners hadn’t travelled there before, and so they would invite them over and even offered them a place to sleep. But that wore off in a few years and it became something normal. Otherwise, I think the exchange of experience was enriching for both sides and that the Czechs had an opportunity to adjust their naive and exaggerated ideas of a free society and of the important role of culture in the West.

It’s apparent from the catalogue that foreign visitors vastly prevailed during the first years, and then gradually more people from Czechoslovakia appear — including Petr Nikl, Jan Svoboda, Pavel Fajt, Martin Janíček and Martin Zet — all of whom you were, incidentally, often working with. Was this because it was hard to find someone who wanted to take part or due to some other reason?

It wasn’t easy for me to arrange something in the Czech Republic. Because of my job and family, I had a limited amount of time for organization, limited funds and a limited period of time that I could spend outside Amsterdam. We were just at the dawn of the luxury of immediate email communication, and it was expensive to use the phone. That’s one reason. Another thing was that the way of working in a very specific environment and in shared living arrangements is certainly not for everyone. Not everyone could afford to take a trip somewhere for an extended period of time, to go to a fourteen-day symposium. Even today’s artists usually have some kind of job — the privilege of free time wasn’t and isn’t a given. Though in the beginning I felt that the living costs weren’t so high in our country, in 1995 a change occurred and we all became more cost-conscious. If there wasn’t support for a given event in the form of a contribution, not everyone could afford it. Moreover, the residencies were still an unknown concept, so it first had to be somehow shaped and experienced. The Czechs that attended were simply those who were intrigued by the event and who were interested in or felt the need to participate. Petr Nikl told me he took the principle from Plasy and transformed it in the Rudolfinum Gallery into the Nest of Games exhibition; Pavel Fajt and Václav Cílek organized a series of site-specific concerts in Santini’s architecture to name a few. The Plasy context accommodated a different type of creation than that of the gallery or museum, and this probably also influenced the makeup of the kindred circle.

The residencies continued for a certain time at the chateau in Čimelice, as there was some cooperation with the Soros Center for Contemporary Arts at that time. The development of the Soros Center for Contemporary Arts (SCCA) that operated in Prague since September 1992 (first at the Olšanka hotel building), and that of Hermit was concurrent, but contacts were made later, not in the early 1990s. Why?

We worked with the Soros Center for Contemporary Art right from the beginning, since it was the only specialised organization, aside from the Ministry of Culture, whose door we could knock on. At that time the SCCA did not have a residency programme. We tried to convince the director, Mr. Ludvík Hlaváček, that it was a good idea to join the existing infrastructure, providing accommodations, studio spaces and facilities for foreign artists that were created in Plasy with the project of a strong international network for Central and Eastern Europe which the SCCA could oversee and manage. Although the Soros Center was created in 1992, the residencies weren’t organized until 1997 when the Center moved to its Jelení headquarters in Prague 6. Indirect residency exchange activities were happening even before that. Just like the Hermit Foundation, the SCCA became a member of the international association Res Artis and artists from Central and Eastern Europe came to Plasy several times thanks to the grants from the Soros network. In the end, however, we were unable to achieve any kind of connection that could have ensured the continuation of the Plasy project. The SCCA received in 1998 an offer to use the Schwarzenberg chateau in Čimelice. Martina Smeykalová, who worked with us in Plasy, went over and started working there. The residency programme in Čimelice lasted until 2002.

It’s strange that there wasn’t tighter cooperation with the SCCA, since the focus would have been quite similar: international and interdisciplinary projects. In Soros’s case perhaps more focused on new media and politics, in Plasy’s case more focused on audio art. You yourself later worked directly at the Soros Center.

The SCCA’s dramaturgy was governed by the projects that fit into the entire programme of the Soros network. New media and the political art were exhibition concepts. Ludvík Hlaváček was more interested in creating the center’s own residency programme and had at that time the possibility to get funding and managed to invest it into the Schwarzenberg chateau in Čimelice. I worked in the SCCA at Jelení for some time after I left the National Gallery — i.e. from the end of 1999. I took over the program of Artlab, small media lab, and also helped a little with the residencies. We had four employees altogether, Dana Recmanová took the residency programme over from Kateřina Pavlíčková and oversaw its operation. The only continuity with Hermit was through Martina Smeykalová (Tomášková) who worked for a year as an assistant of the SCCA residencies program in Čimelice Castle.

This translation has been reviewed by Vít Bohal * and Miloš Vojtěchovský.

Lenka Dolanová (born 1979) is art historian, curator and researcher in arts and new media arts, was teaching experimental film and video at Charles University in Prague and at the Faculty of Fine Arts of Brno University of Technology. She was researching mostly in the field of early video art histories, with a specialisation on the work of Steina and Woody Vasulka. Between 2005 and 2006 she was Fulbright researcher at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. PhD at the Prague Film School FAMU. Member of Publick and Yo-Yo. Lives in Jihlava where she works as a curator at the Regional Gallery and runs the residency program in Kravín.

Miloš Vojtěchovský (born 1955 in Prague) is a curator, art historian, sound and audiovisual artist. Graduated in Art History and Aesthetics from Charles University in 1981. In 1989 conceived and worked as a researcher, co-producer and co-author of the interactive educational pilot project Orbis Pictus Revised, commissioned by ZKM Karlsruhe (the Imaginary Museum Project, (in collaboration with Tjebbe van Tijen and Rolf Pixley). In 1991 he initiated together with Jiří Kornatovský The Hermit Foundation a.k.a. The Center for Metamedia - an international multidisiplinary art residency project at Plasy Monastery, which lasted until 1999. He was the curator of contemporary and media art at The Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art at the National Gallery in Prague (1997-2000), and with Jaroslav Anděl, among others, he co-curated the exhibition project Dawn of the Magicians (1997 -1998). He curated the program of the Media LAB at the Center for Contemporary Art in Prague (1998-2004). Between 2000 and 2004 he was engaged in the internet art radio and the netcasting project Radio Jelení, which consequently morphed into the streaming and communication audio and video project Lemurie TAZ. Between 1997 and 2005 he has lectured on new media, contemporary art, media theory and history at The Faculty of Fine Arts at the Technical University Brno. Since 2004, he has taught media art history and theory of art at the Center for Audiovisual Studies at Film and Television Faculty at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. He was as well the curator of the program at the Gallery Školská 28 (2009-2012). Together with Roman Berka, he founded the educational academic platform The Institute of Intermedia for reasearch in contemporary arts, science and technology. Vojtěchovský has been publishing texts in Czech, Dutch, German, and English art magazines and journals (His Voice, Literární noviny, Atelier, A2). In 2009 he, together with Peter Cusack, started up the ongoing project Sonicity (Sounds of Prague), dedicated to the psychogeography and soundscapes. He curated the Czech section in the international networking project Soundexchange, co-curated the symposium and festival vs. Interpretation held in Prague, 2014 and was one of the initiator of the project Frontiers of Solitude.